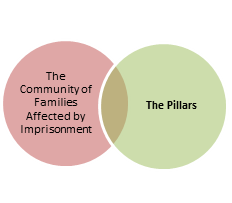

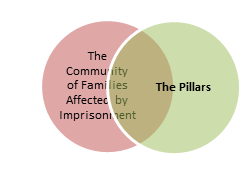

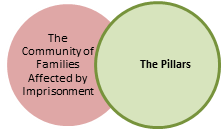

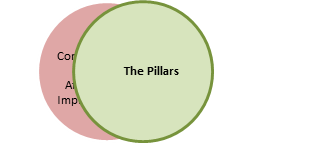

The four previous Sub-Chapters (2.3.4, 2.3.5, 2.3.6, 2.3.7) described the individual Pillars. I will now explore the effects of their dominance in society in general but in particular as it pertains to the Focus Group.

To begin, this brief example will illustrate how each of the Pillars feeds the others’ needs in the area of families affected by imprisonment and involved in serious crime.

Let us say that there is a large housing estate where there is a lot of criminal gang activity including murders over a period of some years. The media report this activity (including the methods by which criminals operate, the precise and sometimes gruesome details of the ways people die in murders, the personalities involved, the danger to children, and the operations and investigations of the Gardaí, court proceedings etc.) with great enthusiasm. The more lurid the descriptions the higher the sales!

The experts called in to analyse (mostly in the media) why the situation in a particular estate got to the stage where there are gangs fighting each other and/or how children drop out of school and get sucked into drug addiction and crime, are probably senior Garda officers, criminologists, or sociologists.

Opinions on what should be done to protect such children are offered by psychologists, social workers and community workers guided usually by academic training. These opinions are offered to the public in articles, comments, critiques, sound-bites etc. The ‘who-what-where-when-why’ is debated endlessly, and sometimes research is funded to consult with people as to what should be done.

Concerned professionals may buy in intervention or diversion programmes for youth, single mothers, young men, addiction, anger management etc. – almost always developed in academia or private educational offshoots of academia.

Opposition politicians get publicity criticising Government politicians who might have, (say) closed a Garda station in the area, and similarly Government politicians defend all the great work that they have done in preventing crime and, through the media again, promise new initiatives for the future.

But through it all – it is highly unlikely that the potential of the people to come up with a solution themselves is ever seriously considered.

The people themselves are actually a community of mutual support that the Pillars, almost always, totally discount. If we practitioners don’t or won’t recognise the extent to which people care for each other, and the value of that, we’ll always be functionaries, maybe very nice functionaries, but functionaries nonetheless.

(I have already mentioned, and will mention again a research publication from 2010, entitled How Are Our Kids at the end of this Chapter that pointed to the extent of that caring).

If we retreat to a fearful place on encountering what we might label as dysfunction, we’ll miss out on discovery – to our own loss!

If, however, we are alert to, and curious about such matters, and are prepared to put aside the sense of superiority that might come from formal education and status in society (that, in fairness, we may be unaware of) we have a great opportunity to do better work and perhaps discover new potential in ourselves too – hitherto unrecognised and untapped.